About half a year later, the Opportunity landed in the Meridiani Planum region of Mars, tasked with the mission to travel for 1,100 yards (1 km) and last for 90 days.

As it turned out, MER-B, affectionately called Oppy, lasted for a total of 15 years and trekked across Mars more than any other human-made vehicle. It set records, beat odds and uncovered mysteries. And then it died.

In mid-February 2019, NASA officially pulled the plug on the Opportunity, following seven or eight months of constant efforts to revive it. Opportunity’s demise marks the official end of the most important planet exploration machine ever constructed.The Rover

Opportunity was part of the Mars Exploration Rovers program that called for two identical machines to be sent to Mars. It’s brother, Spirit, landed in the Gusev Crater on the opposite side of Meridiani Planum three weeks before the Opportunity.

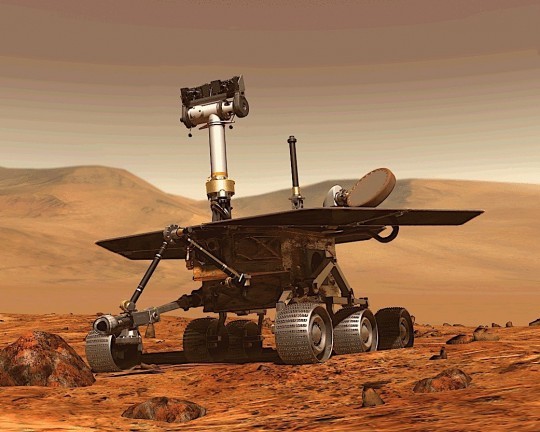

Both machines are about the size of a golf cart, measuring 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) high, 2.3 meters (7.5 ft) wide, and 1.6 meters (5.2 ft) long. Fully equipped, the MER rovers weigh 180 kilograms (400 lb).

Power, and the main cause for Opportunity’s demise, comes from solar panels. Energy captured from the sun is used to power all the rover’s systems.

The machine if fitted with a rocker-bogie fitted with six wheels. Each of the wheels spins thanks to individual motors, a feature which also allows front and rear steering and operating tilts of up to 30 degrees.

The machine if fitted with a rocker-bogie fitted with six wheels. Each of the wheels spins thanks to individual motors, a feature which also allows front and rear steering and operating tilts of up to 30 degrees.

The top speed of the MER rovers is so small that they can be easily regarded as the slowest machines ever made by man: 5 cm per second (2.0 in/s). Given the rough terrain on Mars, the top speed was seldom actually reached. The Opportunity and Spirit usually traveled at average speeds of only 0.89 cm per second (0.35 in/s).

For the tasks of exploration, the Opportunity is equipped with several types of cameras (navigation, hazard avoidance, panoramic), and specialized tools: a Microscopic Imager, three spectrometers (thermal, Mossbauer and X-ray,) a rock abrasion tool and magnet arrays.

Being launched in the years immediately following the events of 9/11, both the Spirit and the Opportunity carried with them to Mars small pieces of the World Trade Center, in the form of aluminum cuffs serving as a cable shield on each of the rock abrasion tools. The Mission

At first glance, the purpose of sending Opportunity to Mars was pretty straightforward. All the rover had to do was look at rocks and determine their composition. But from its findings, NASA and world scientists were to determine if our neighboring planet ever had liquid water.

In a larger sense, the goal of the mission was to set the groundwork for a possible human arrival on Mars. By looking at rocks, Opportunity could make humans understand whether it is possible to find liquid water, but also learn more about the planet’s climate and geology.

During its 15 years stay there, Opportunity exposed the surface of 52 rocks. Using a brush, it dusted off an additional 72 rocks, getting them ready for spectrometer and microscopic analysis.

During its 15 years stay there, Opportunity exposed the surface of 52 rocks. Using a brush, it dusted off an additional 72 rocks, getting them ready for spectrometer and microscopic analysis.

It’s primary mission, to determine whether water did flow on Mars, was completed when it found hematite, a mineral that is formed in the presence of water. This finding determined the Endeavour Crater could have been a lake of fresh water.

While on Mars, the rover broke a few records as well. For one, it is responsible for sending back around 217,000 images of the planet, including 360-degree color panoramas. The Drive

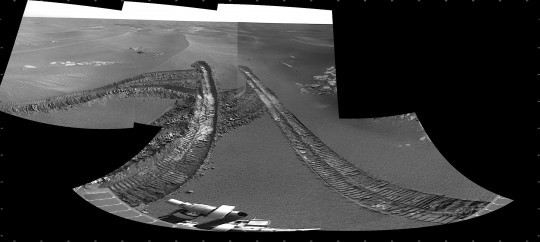

Oppy set the record for the longest one-drive on Mars in March 2005, when it floored it and moved 721 feet (220 meters) across the Martian surface. In all, the Opportunity travelled farther on alien soil than any other Earth-machine: 28 miles (45 kilometers).

It all started in the Eagle crater in Meridiani Planum, where the rover successfully landed and discovered blueberries, sedimentary formations that can only form in water. It then moved to Endurance crater, to perform in sequence stratigraphic section of Mars’ geological past.

Endurance was to be followed by Victoria, located kilometers away. The journey there was both long and dangerous, as Oppy got stuck in a dune of windblown material. To be able to break free, the rover had to move in reserve, yet another premiere for the human machines exploring other planets.

Once the dune issue solved, the rover hit its next major obstacle, a half-mile diameter crater, its target: Victoria.

Once the dune issue solved, the rover hit its next major obstacle, a half-mile diameter crater, its target: Victoria.

As the Opportunity was just standing there, contemplating what to do, the HiRISE camera up in orbit got a photo of it. It was the first image of a Martian rover taken from space.

Opportunity spent a year on the edge of the Victoria crater looking for the best way to cross it, and another year inside Victoria itself.

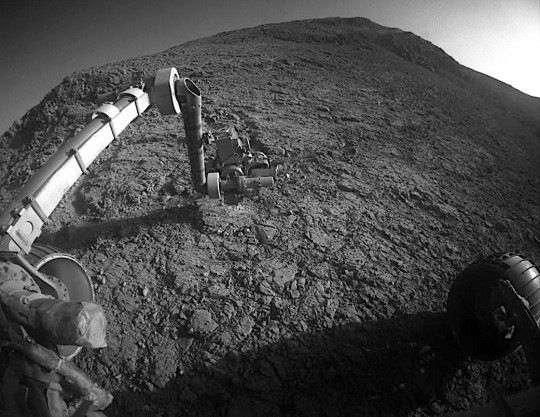

Up next was the Endeavor crater, 20 km away, a journey that would take several years to complete. To avoid dangerous areas, a swirling path had to be devised so that the rover would make it to its destination. Once at Endeavor, the rover discovered gypsum veins for the first time.

Once its job there was complete, the rover set out to Perseverance Valley, the place that was to become its final resting place. The End

At the beginning of June 2018, huge clouds of dust begun rising up above the Martian surface, stirred by heavy winds. In less than three weeks, the storm was so large that it engulfed the entire planet. It would last for about a month.

Being powered by sunlight, Oppy found itself with no means to feed, so it entered minimal operations mode to ride out the storm. The idea was to come back online after Martian winds cleared both the sky and the solar panels.

Being powered by sunlight, Oppy found itself with no means to feed, so it entered minimal operations mode to ride out the storm. The idea was to come back online after Martian winds cleared both the sky and the solar panels.

Oppy did not recover from the shutdown. Nobody knows if it’s buried under tons of sand, or operational, but unable to communicate, or outright dead.

After trying for months to reactivate it, NASA gave up in February 2019.

As a result, until the next rover lands on Mars in 2021, there’s only one other human-machine moving around there: Curiosity.